During Laetitia Gorra’s stint as head of interior design at The Wing, she was focused on designing inclusive spaces that centered the people that coexisted within it. “We learned so much as designers for that space [about] how people use physical spaces to build community,” she says. Now, as the founder and CEO of Roarke Design Studio, she caters to clients that want offices that prioritize the happiness and well-being of their employees. “I feel like employers are thinking through employee happiness much more than they were a decade ago,” Laetitia insists. “They’re thinking about it in terms of it being a retention tool and a hiring tool. If you are setting your employees up for success, that’s the ultimate goal. I think so much of success is your surroundings. How are you functioning in these spaces?”

Kara views the corporate fetish aesthetic as an inherent subconscious concept that so many creatives are gravitating toward out of a sense of familiarity. “When you hear the word ‘office,’ I immediately go to fluorescent lights, low ceilings, carpet and a cubicle,” Kara says. “Aesthetically, it also adds to the secure aspect of it. I feel like if we were to shoot in a modern office, it wouldn’t give it that punch it needed.” Obviously, what we’re seeing in this imagery is the “fun” parts of being in the office. But as we, the working class, find ourselves returning to the office at full speed, the reality is that these settings don’t look or feel the same as before the pandemic. What seems to be missing from the equation of the “new normal” that is hybrid working in its current iteration is the structure, routine, and friendships that are attached with the outdated office environment. Instead, what we now have is a void that stems from a need for third places.

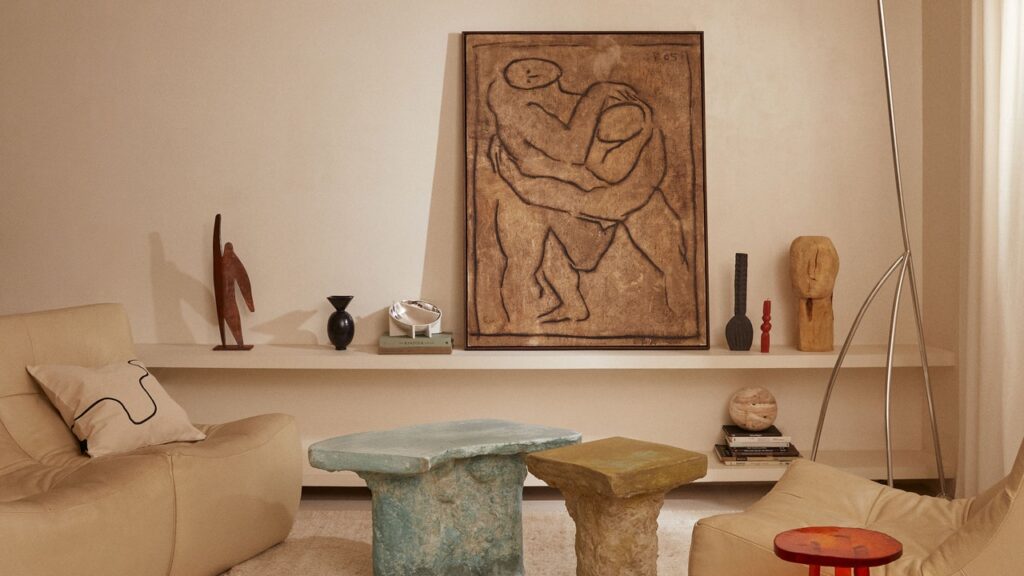

According to Laetitia, the main task of the designer is to figure out how to incorporate a company’s culture into how they build out these spaces so employees will actually want to come into the office. Given the growing number of people that are less motivated to return to the office, it’s ironic that the office has still managed to become a modern-day muse. Last year, Globest reported that vacancy rates for offices in Manhattan would rise to 20% through 2026. Rather than working remotely from home, businesses like Houseplant and Ghia are opting to work in homes by converting houses into headquarters suitable for their employees to maintain productivity.

On the other end of the spectrum we still see tech empires going for the college campus style, or as professionals prefer to call it, the corporate campus. As Docomomo states, corporate campus architecture emerged during the postwar boom; as the middle class moved to the suburbs, legacy companies seized the opportunity for “expansive campuses, large parking lots, tax breaks from local governments, and a chance to rebrand themselves.” On this note, Amy asks an important question: “What are the amenities of a [corporate] campus beyond what you need to get your work done?”